Nisha Midha has been an intern with GWP since the beginning of May 2017. She recently read GWP’s new Technical Committee Background Paper “Measuring transboundary water cooperation: options for Sustainable Development Goal Target 6.5” and found herself fascinated by its content. In this post, she reflects on the importance of thinking critically on how we measure success, the use of indicators for reaching SDG targets, and just how big the SDG targets really are.

At first glance, the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) are daunting. To make the SDGs more tangible and approachable, each SDG has an associated set of targets. Similarly, to help monitor the progress towards each SDG target, each target has one or more indicators. The purpose of these indicators is that they are measurable, can be evaluated, and ultimately, will help us determine – locally, nationally, and globally – when an SDG has been achieved. Sounds simple, right?

At first glance, the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) are daunting. To make the SDGs more tangible and approachable, each SDG has an associated set of targets. Similarly, to help monitor the progress towards each SDG target, each target has one or more indicators. The purpose of these indicators is that they are measurable, can be evaluated, and ultimately, will help us determine – locally, nationally, and globally – when an SDG has been achieved. Sounds simple, right?

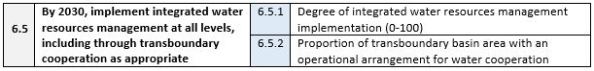

Let’s look at SDG 6, which is to “ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all”. It has 6 targets, all of which are equally important. However, SDG Target 6.5 is of particular interest to GWP. It states: “by 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate” [1]. There are two indicators for SDG 6.5 which aim to measure implementation of IWRM (6.5.1) and transboundary cooperation (6.5.2), as can be seen below [1].

GWP published Technical Background Paper No. 23 in June 2017, which specifically examines SDG indicator 6.5.2. As discussed in the paper, it is imperative that the definition of each component of the indicator, such as “operational”, is clearly understood. Otherwise, it is likely that results submitted from country to country will be highly variable and results will not be comparable.

GWP published Technical Background Paper No. 23 in June 2017, which specifically examines SDG indicator 6.5.2. As discussed in the paper, it is imperative that the definition of each component of the indicator, such as “operational”, is clearly understood. Otherwise, it is likely that results submitted from country to country will be highly variable and results will not be comparable.

What does indicator 6.5.2 hope to measure? It’s obvious that surface water basins and groundwater aquifers do not respect international borders. This results in shared, or transboundary, waters between nations; 310 transboundary basins and 500 transboundary aquifers exist [3]. In order for SDG 6 to be fully accomplished, nations must cooperate over these shared waters. Indicator 6.5.2 comes to the rescue: monitoring will yield an in-country percentage “of transboundary basin area with an operational arrangement for water cooperation” [1], where operational arrangements include joint management plans, information exchange, regular meetings, and joint organisations [4]. But how do we define and measure cooperation? How regular do these meetings need to be? Does information exchange truly dictate better shared management of a transboundary water?

Hopefully at this point you are beginning to see the importance of definitions. The recently published paper I read analyzes three methodologies that approach the measurement of transboundary cooperation through different perspectives. One of the three methodologies has already been planned and developed (by UNECE and UNESCO), but is critiqued by the paper’s author (Melissa McCracken) as being prescriptive and lacking flexibility to capture all forms of transboundary cooperative efforts. The second method analyzed is an adaptation of the UNECE and UNSECO methodology, while the third method is an altogether different approach proposed by Dan Tarlock in GWP’s Technical Background Paper No. 21.

McCracken tests each of the three methodologies by doing calculations using real examples of transboundary basins and aquifers in three countries: Bangladesh, Honduras, and Uganda. She is able to compare and contrast the results of the three methodologies, especially scrutinizing whether the numbers reflect the actual transboundary context in each country. McCracken’s examination reveals some key findings on the best way forward for calculating SDG indicator 6.5.2, which I will leave for you to read. The real reason for this blog post is to zoom out from her paper and examine monitoring the SDGs from a broader perspective.

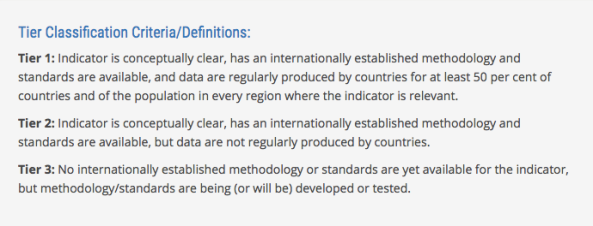

We have so far been discussing a single SDG indicator, but SDG 6 has 11 indicators. And SDG 6 is just one of seventeen SDGs! In total, these 17 SDGs are represented by 241 indicators. Two hundred and forty-one. Each of these indicators are complex and, similar to 6.5.2, could be highly contested on how to measure them. Though this can be overwhelming, I find reassurance in the recent mobilization of efforts to develop the best methodologies for measuring each indicator. For example, UN-Water, the coordinator of SDG 6 monitoring, involved experts from all over the world to develop and optimize the SDG 6 indicator methodology. Indicator 6.5.2 was recently promoted to a “Tier II” indicator from “Tier III”; this means that while the methodology may be closer to being established, a key and missing component of monitoring transboundary cooperation is that the required data is not being tracked in all countries [6]. UN-Water has now been working tirelessly to pilot test SDG 6 monitoring in five countries by establishing country teams, training them, and collecting indicator data [5]. Ultimately, these first attempts at monitoring will reveal required adjustments in the methodology to improve data outcomes; GWP Tech Paper No. 23 is a key contribution to this effort.

UN-Water has now been working tirelessly to pilot test SDG 6 monitoring in five countries by establishing country teams, training them, and collecting indicator data [5]. Ultimately, these first attempts at monitoring will reveal required adjustments in the methodology to improve data outcomes; GWP Tech Paper No. 23 is a key contribution to this effort.

To conclude, I enjoyed the paper because it reminded me that we will need to be critical of how we measure our progress towards sustainable development. While the procedures for measuring SDG indicator 6.5.2 have already been advanced, McCracken recommends certain ‘tweaks’ to the related definitions and methodology to ensure we are monitoring in the best possible way. Achieving sustainable development in 13 years is going to take a concerted global effort of many small efforts just like those made by this paper and the individuals behind it. This is key – there will always be the need for individual actions to accomplish progress. Since countries are responsible for monitoring advancement towards the SDGs, even as citizens we can encourage our national decision-makers to invest and implement the best data collection methodologies possible.

I applaud McCracken and those who work relentlessly to scrutinize our SDG path forward. However, I also believe that eventually we will need to roll up our sleeves, stay positive, lean on each other, and get to work. Next stop: sustainable development!

[1] United Nations. (2017). Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. SDG 6. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg6.

[2] Global Water Partnership. (2017). Measuring transboundary water cooperation: options for Sustainable Development Goal Target 6.5. GWP TEC Background Paper No. 23. Retrieved from http://www.gwp.org/globalassets/global/toolbox/publications/background-papers/gwp-tec_23_measuring-transboundary-water-cooperation.pdf.

[3] Wolf et al. (Forthcoming). Revisting the World’s International River Basins.

[4] United Nations-Water (UN-Water). (2016). Step-by-step Monitoring Methodology for Indicator 6.5.2. Retrieved from http://www.unwater.org/app/uploads/2017/05/Step-by-step-methodology-6-5-2_Revision-2017-01-11_Final-1.pdf.

[5] UN-Water. (2017) Country process for SDG 6 monitoring (pilot). Retrieved from http://www.sdg6monitoring.org/news/country-process-for-sdg-6-monitoring-pilot.

[6] UN-Stats. (2017). IAEG-SDGs. Tier Classification for Global SDG Indicators. Retrieved from https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/tier-classification/.